Field-based learning in Costa Rica

OTS Tropical Plant Systematics Class 2016

Learning outside the classroom is something we’re all growing more accustomed to at the moment. The coronavirus crisis has plunged us all into a new world where we are adapting, ready or not. I am inspired by new initiatives for informal education and reflecting on my own non-traditional learning environments. I am also grieving the missed opportunity to return to my favorite field-based classroom, Costa Rica, this summer.

I studied abroad in Costa Rica in 2006, and what I took away from that semester was more than I ever gained from a classroom. I spent a semester based in Monteverde’s Cloud Forest Reserve, trekking up and down both coasts of Costa Rica and into Panama’s Bocas del Toro Islands, even living in a family’s home for a month-long Spanish immersion. My first experience with tropical ecosystems and plant diversity inspired me to change my major from pre-med to ecology and evolutionary biology. A decade later I found myself working on my PhD, albeit always dreaming of being back in the rainforest.

OTS Tropical Plant Systematics 2016: Biological Field Station sites

In June of 2016 I was accepted into the Organization of Tropical Studies (OTS) graduate Tropical Plant Systematics Course in Costa Rica, a research-based field program. For five weeks, 13 graduate students, including myself, were immersed in plant systematics, studying under professors from all over the world. I was honored, excited, and grateful to have been invited back as a Teaching Assistant this summer, but alas, the course has been cancelled. There’s nothing quite like being in the middle of the forest, staying in a biological research station, and learning the ecosystem through feeling it. Since I can’t be there this summer I’m just going to dream of being back there. The OTS course treks students to four different research stations, each unique and special. This blog will focus on the stations, because the plants, the professors, and my classmates from this course are deserving of their own post.

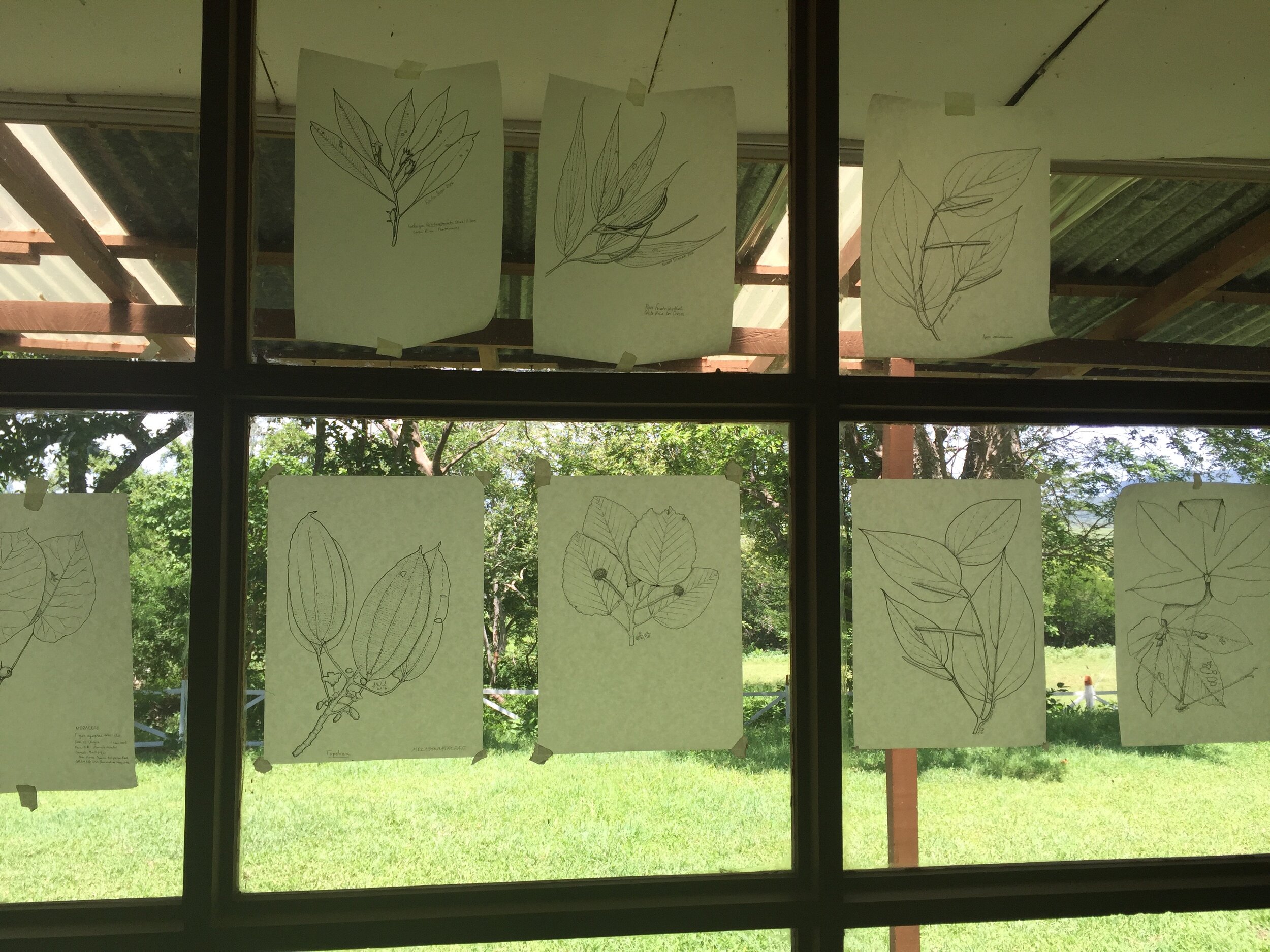

Las Cruces— Located near the Panamanian border. This station is immersed in a mid-elevation (1100 m) rainforest and covers 216 hectares*, protecting one of the largest remaining fragments of tropical wet premontane forest in southern Costa Rica. Founded in 1962 as a botanical garden, there’s an extensive collection of native and imported tropical plants. Here we had our “botanical boot-camp” and learned the important skill of identifying woody plants without any reproductive material (flowers or fruits). We saw many representatives of the Zingiberales, the order of plants that contains the banana (Muscaceae) and ginger (Zingiberaceae) families, and many other iconic tropical monocots. Here we also tried our hand at botanical illustration.

*1 hectare =2.5 acres

Cuericí— Located in the Cordillera de Talamanca mountain range. This station is in a pristine tropical oak forest (2400 m). Surrounded by cloud forests, this area has both primary and secondary forest—when you’re standing in the midst of each of them it’s easy to note the differences. Primary forest has never been cut before, where secondary generally grows where pasture once was. Bordering Los Quetzales National Park and serving as a corridor for migrating birds and many endangered species, this station is very remote. There’s a homemade hydroelectric plant that provides electricity, though only a wood stove heats the buildings. Nearby is the Talamanca páramo, a high elevation (~3000 m) tropical montane ecosystem found above the tree line. Globally, páramos are unique and very diverse, in part due to the high temperature fluctuation. The days are warm and sunny and nights get below freezing.

Palo Verde— Located in northwest Guanacaste. This station is situated between an extensive marsh and a seasonal dry forest, inside of Palo Verde National Park. The park covers 20,000 hectares and harbors one of the most important Central American wetlands and intact patches of tropical lowland dry forest. Here we learned how to make a forest transect for the purpose of counting the number of species in a given area. If you “swim” out to the middle of the marsh, you’re surrounded by some of the most fantastic views. Ask anyone who has been to Palo Verde about the ‘wildlife’ and they’ll probably tell you about the mosquitoes and scorpions, however howler and white-faced monkeys are also found here.

La Selva— Located near Puerto Viejo in the Atlantic lowlands this station sits around 60 m in elevation. Covering 1500 hectares, there are over 2,000 species of vascular plants here. Here we took advantage of the extensive paved and dirt trails, practicing our plant identification skills. The herbarium on site houses more than 10,000 specimens of dried, pressed plants, which helps when you don’t know what a particular plant is.